Massive Attack: 1991

Massive Attack's Blue Lines (collage by Laura Fedele for WFUV)

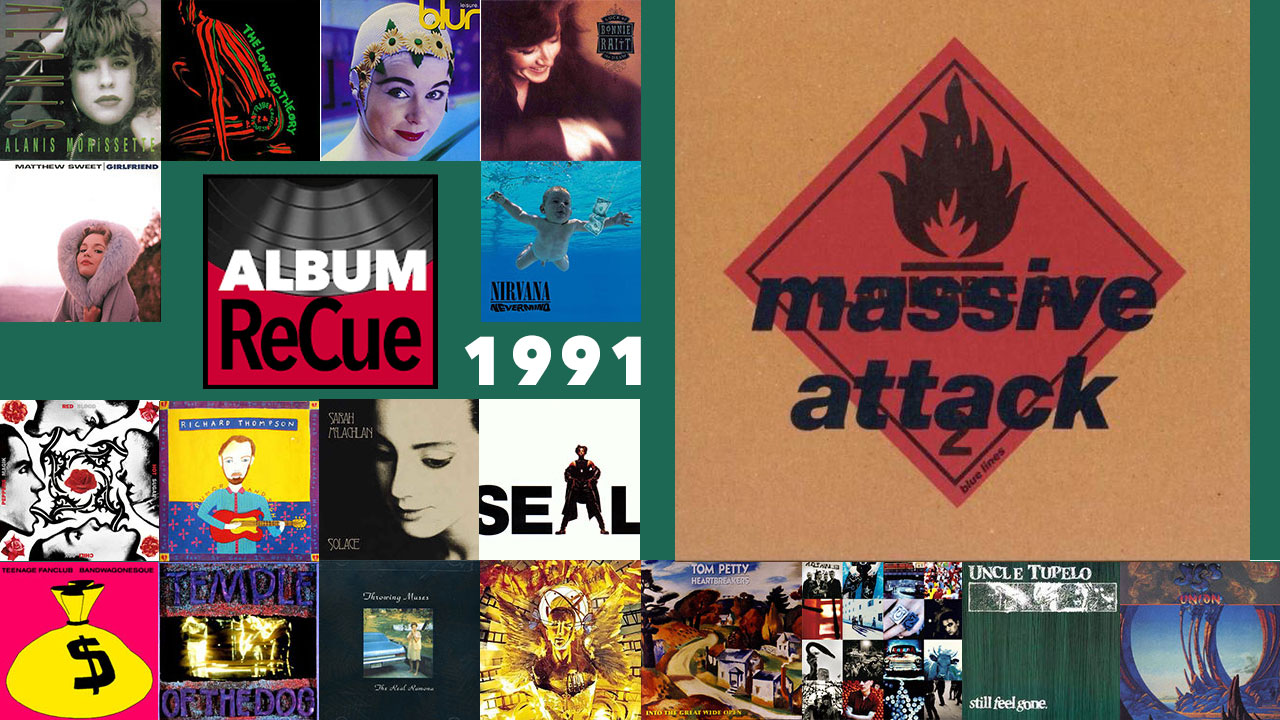

“Album ReCue” for Throwback Thursday celebrating 30th anniversaries: 1991 releases chosen by FUV hosts. Above, listen to Alisa Ali's conversation with Corny O'Connell about his selection, Blue Lines, the watershed debut from Massive Attack, and below, Kara Manning’s overview of that release.

Thirty years ago, as the Gulf War consumed global headlines, a young band from Bristol released an astonishing second single of spiralling despair and excruciating beauty, “Unfinished Sympathy.” The BBC, in an overabundance of caution, restricted radio hosts from saying the group’s entire name, calling them merely “Massive” — the track was even first released by their label with that truncated name.

That band was, of course, Massive Attack, founded by Robert “3D” Del Naja, Grant “Daddy G” Marshall and Andrew "Mushroom" Vowles, three members of The Wild Bunch sound system, an eighties collective of Bristol-based DJs, musicians, producers, and visual artists that also included a gruff-voiced rapper named Adrian “Tricky” Thaws and producer Nellee Hooper, later of Soul II Soul. As The Wild Bunch split, Del Naja, Marshall and Vowles expanded their circle as they began recording their 1991 debut album, Blue Lines, in Bristol and London, looping in collaborators they knew, such as singer-songwriter Shara Nelson, Tricky, reggae master Horace Andy, and co-producer Jonathan “Jonny Dollar” Sharp. Associates from The Wild Bunch, like Claude “Willie Wee” Williams and Tony Bryan, were pulled into the fray. Even Massive Attack’s studio dogsbody had cred — it was Geoff Barrow, who went on to co-found Portishead the same year as Blue Lines’ release.

Neneh Cherry, who worked with Del Naja and Vowles on her own debut, 1989’s Raw Like Sushi, became a behind-the-scenes “arse-kicker,” who got the band into the studio, says Daddy G. (Cherry co-wrote “Hymn of the Big Wheel” with Del Naja, for Andy, and was married to Blue Lines’ executive producer Cameron “Booga Bear” McVey.)

“We recorded a lot at her house, in her baby's room,” Marshall told the Observer in 2004. “It stank for months and eventually we found a dirty nappy behind a radiator. I was still DJing, but what we were trying to do was create dance music for the head, rather than the feet. I think it's our freshest album, we were at our strongest then.”

No hyperbole here: Blue Lines is one of the greatest albums ever released, a darkest-night, visionary masterpiece that seduces thirty years after it first dropped; you can hear its heady undertow in contemporary hip hop, dub, reggae, dance, dancehall, house, soul, funk and scores of subgenres (including the obvious tag of trip-hop, a label the band rejected). But it’s not just Massive Attack’s technical or production prowess, clever samples, or even its deep intellectualism that compels; what makes this album truly mindblowing is the emotional tempest at its core, a kaleidoscope of humor, heartache, rage and redemption, tackling love, loneliness, politics, and an existential melancholia. Massive Attack was a mission, an extended riposte to Thatcherism; to their fans, the band represented a progressive, multicultural Britain: “English upbringing, background Caribbean,” as Tricky raps in “Blue Lines.” But in the early days, the scene wasn’t that simple in Bristol.

“We had our group that we all moved with, so there was always some sense of safety,” Marshall told the Guardian in 2016. “But there was always that thing, you know, of someone out there ready to bash your head in if you stepped out of line. Going back to where we were with Massive Attack and the Wild Bunch, it was always a mixed-race thing, so we were always going into circumstances where it could go either way. Either [Del Naja] could get beaten up for being in the wrong place because he’s in a Jamaican club with me, or I could get beaten up for being a black bloke in a punk club. So we were always treading water in that respect.”

The murmuration of choppy beats that launches lead track “Safe From Harm” is like the landfall of a storm: the sensual tangle of Nelson’s ethereal incantation and Del Naja’s hushed mutter is sinister and gorgeous, an urban freakshow fever dream of “Midnight rockers/City slickers/Gunmen and maniacs.” The arresting “Daydreaming,” the group’s debut single (and what snagged them their Circa label deal), “Five Man Army,” and the title track, “Blue Lines,” are flowing, sometimes playful, conversationally rapped volleys between a rotating cast of Del Naja, Marshall, Tricky, and Willy Wee — sharing spliffs, breakbeats, and dissident whispers. Throughout the album, Nelson and Horace Andy exchange places as wary ospreys circling overhead; in “Five Man Army,” Andy hovers between raps, even warbling a fragment of his own song, 1972’s “Skylarking.”

Few songs in recorded history match the thrilling, arrhythmic urgency of “Unfinished Sympathy,” driven by heaving strings, a slithering bassline, and songwriter Shara Nelson’s holy voice and heart-shattered lyrics. (The song’s transfixing video, directed by Baillie Walsh, was a single continuous shot of Nelson walking down Los Angeles’s West Pico Boulevard). Covers had always been a part of Massive Attack’s DNA — The Wild Bunch made an early impact with their 1987 cover of Bacharach and David’s “The Look of Love” — and in addition to samples and shards of lyrics, Blue Lines also features a fairly straightforward version of William DeVaughn’s “Be Thankful for What You Got” from the seventies with a slightly altered title of “Be Thankful for What You’ve Got,” sung by Tony Bryan.

Blue Lines, this chilled goliath of releases, arrived in a year that also saw a wave of other game-changing albums, including Primal Scream’s Screamadelica, My Bloody Valentine's Loveless, and Nirvana’s Nevermind — hardly slouches when it came to shaking up what was heard on the radio and in clubs. But Blue Lines’ slow-burn mind-melt of psychological labyrinths remains the acme of all music that came out that year and that decade.

And while Massive Attack’s third album, 1998’s Mezzanine, is cited as the group’s pinnacle by some critics, it’s a very different album — yes, brilliant, but riddled with a forboding anxiety, as Del Naja, Vowles, and Marshall acrimoniously warred between themselves. Seven years earlier, the triad of Nelson, Tricky, and Andy (who remained a frequent collaborator over the years) and the collective support team on Blue Lines balanced Massive Attack’s trio of co-founders, buoyed by hopeful ambition and a mad cascade of ideas: the result was sheer perfection.

Listen

WFUV's Album ReCue: Massive Attack's Blue Lines