FUV Essentials: Vin Scelsa on the Summer of Love

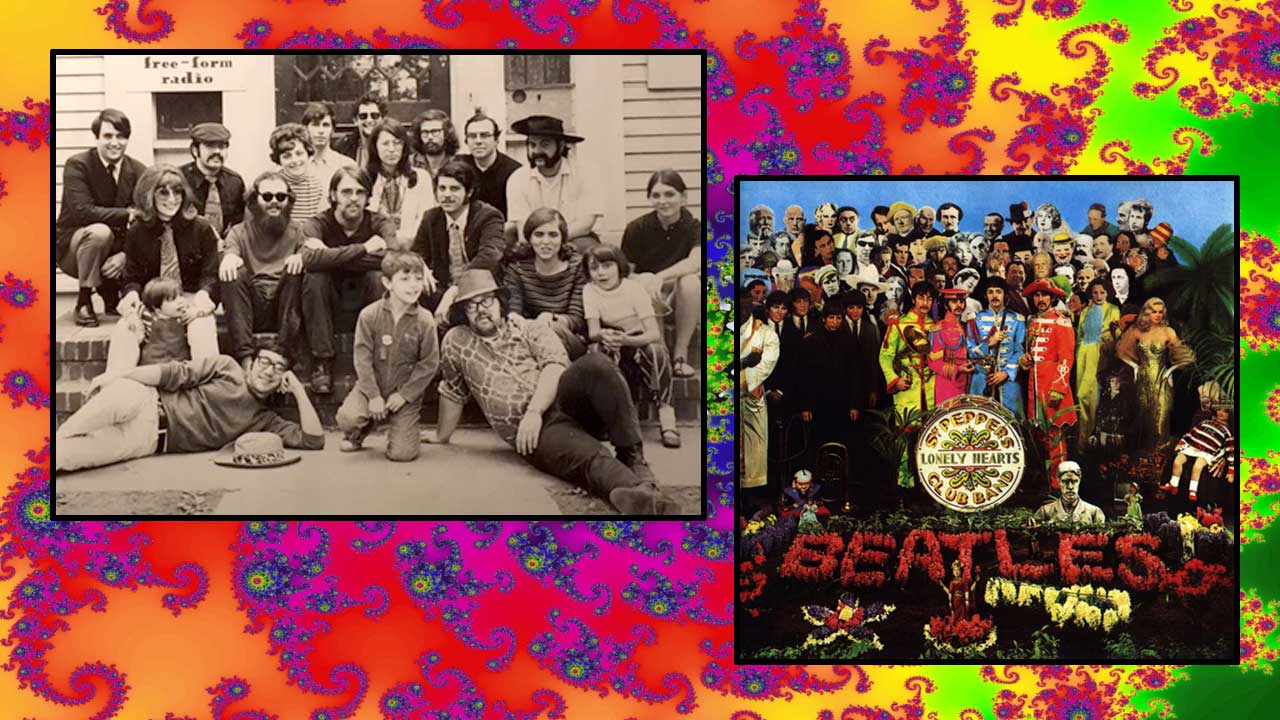

Vin Scelsa (far right, first row) and his soon-to-be-wife Freddie Bauman

[It's been two years since Vin Scelsa, FUV's beloved host of "Idiot's Delight," retired from the airwaves (although he still records the occasional podcast with his daughter Kate). But as the 50th anniversary of the Summer of Love and the Monterey International Pop Festival approached, FUV asked him if he might like to write about that halcyon time, which also marked the beginning of his life in radio. And happily, Vin agreed. - Ed.]

In June 1967 I was 19 years old, working a summer job at the Phelps Dodge Copper Factory in Elizabethport, NJ, under the Goethals Bridge and down the road from the giant, flame-spewing Esso Refinery and its docks. I was going through my Jack Kerouac stage, writing poetry by day and working the night shift as one of a half dozen security guards, mostly older men, some of whom had worked there back in the mid-century days of labor unrest, guys who still knew the secret location of the company’s arsenal. I wore a cop hat, a khaki uniform, and a badge. It was the beginning of the Summer of Love.

As security guards, we spent the night walking tours of the factory equipped with a time clock we had to punch with keys located in each department; this was to prove we had actually walked the tours. In between these walks we were stationed at an outdoor booth on the edge of the complex with little to do besides watch the drunken sailors from every country on the planet stumble back to their ships down on the Esso docks, singing alcohol-fueled anthems in their various native tongues. I spent my downtime trying to read a battered paperback of Desolation Angels. The tours took around 50 minutes. Then we stayed in the booth for 50 minutes. Then we’d walk the tour again. There was always a guard in the booth and another guard walking the complex.

One of the older guards had a large portable transistor radio which he treated like some kind of holy arc. It was a battery-operated AM/FM radio, back when such radios were still quite rare. With great reluctance he it left behind in the booth when he walked his tours, with strict “do not touch” instructions. FM radio was still a rather esoteric medium appealing to stereo buffs and classical music lovers (classical music sounded great on FM radio because the signal was so clean — no static at all, as Steely Dan would sing a decade later). Growing up in New Jersey I listened mostly to Top 40 AM radio – the WABC "All Americans" and the WMCA "Good Guys," and my parents' favorite stations WOR (Dorothy & Dick, John Gambling) and WNEW-AM ("The Milkman's Matinee"). My ignorance of FM was fairly typical: the medium had not yet entered the mass consciousness. New cars still came only with AM radios as standard equipment; if you wanted FM in your car, you paid extra.

So it’s June 1967. Like every other young person in America I had spent the previous months anticipating the release of a new Beatles album. The word on the street was that the Beatles were about to change the game … again. In fact I was having trouble concentrating on the Kerouac book because of this overriding distraction. So after much begging and promising to be careful with it, I got permission from that guard to listen to his “precious” radio during my down time in the booth, on the off-chance that something new from the boys would hit the airwaves in the middle of the night.

The first time I ever in my life listened to FM radio I started tuning the dial and discovered there wasn’t really all that much to listen to. Mostly just the same stations as on AM, but with different frequencies and the letters “FM” added to their call names, simulcasting the same programs on both bands. But halfway up the dial I heard something that was unmistakable: the Beatles. At least the voices sounded like the Beatles. But the music was, well, something else again.

The song was not familiar, so I figured this had to be from the new album. It’s here! Yes! I was ecstatic. I cranked up the volume and a strange mutation of rock and roll washed over me. The song ended and I waited for the deejay to come on and tell me all about it. But, no … another unfamiliar Beatles song played. And then another. And another. All flowing together like they were part of a much bigger … well, something else again. Finally the music stopped after a song that seemed to be about a circus. Surely someone would speak now. Surely someone would say something about this extraordinary work.

I waited. Finally I heard a series of unique sounds I never thought I would hear on the radio: the unmistakable sound of the stylus being lifted from the record's surface – click! – and then a slight thunk as the record was turned over and placed back on the turntable and then the unmistakable click of the stylus being returned to the disc. Followed by … a distinctly exotic music, a whining instrument of some sort and then a sound like the percussive flutter of angel wings and then a voice that sounded like a Beatle, but also like nothing any of us had ever heard before. And the pattern continued. One song flowed into another song into another song. And still no one spoke. Finally I had to leave the booth to walk my tour. When I got back almost an hour later I flipped the radio on and, sure enough, the same songs were still playing on this mysterious radio show. The pattern continued throughout the night. I never heard anybody speak, either to identify the station or the music. What was this?

Finally, with dawn breaking over the Arthur Kill and the shift coming to an end I heard again what I now recognized must be the album's final song – a majestic, convoluted, almost frightening piece that ended with the striking of a long orchestral chord which took forever to fade. Followed by … silence. Pregnant. Meaningful. Like a Pinter play silence. And then, finally, whispery breathing, out of which a gentle friendly male voice quietly said “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. The new Beatles, cabal.” Cabal? Another long pause. Then he said “This is Radio Unnameable. I’m Bob Fass. Time to split. Bye bye.” He recited a statement of technical jargon and signed listener-sponsored WBAI off the air until later that morning. I was hooked.

I saved money from a couple of paychecks and bought my own AM/FM radio and listened to Bob Fass every night during what became known as the Summer of Love. I came to understand that Bob knew how to play the radio the way an inspired musician plays an instrument. And like a good musician, Bob knew about the importance of the silence between the notes. And like the trained actor that he is, he knew how to draw in his audience, gain their trust, and create a visual theatrical world in which every audio tool could be used to create this indescribable flow of a show, this Radio Unnameable. It was only right that Bob introduced his “cabal” to Sgt. Pepper, just as he would introduce us to so many great musicians and so many wonderful creative spirits over the years. He understood the bond he had created with strangers in the middle of the New York City night. And those strangers, through Bob, recognized the existence of each other in a time of incredible social and artistic upheaval. I had always been fascinated by New York radio's unique voices – William B. Williams, Klavan and Finch, Cousin Brucie, Scott Muni, Murray The K and, of course, Jean Shepherd. And now I had an actual hero, Bob Fass.

In early September the job at Phelps Dodge ended and I returned to school, a small liberal arts college in East Orange, New Jersey called Upsala, which I had begun attending off-and-on two years earlier mostly to be with my girlfriend (we married in 1970 and are still together). That semester she and I joined the staff of the college poetry magazine, which was located on the first floor of a small house on the edge of campus. I soon discovered the existence of Upsala's 5000 watt FM radio station on the second floor of that building. In early November, after I convinced the student manager of the station to give me a Saturday overnight slot, I did my first radio show on WFMU. It was called "The Closet." It was the first show in what would become a 48-year-long career in New York radio. It was my pale imitation of Bob Fass's "Radio Unnameable." On that first show I remember playing the Mothers of Invention, the Grateful Dead, the Fugs, lots of Bob Dylan — and any number of tracks from the Beatles' Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band.

Vin Scelsa

June 2017

Listen to Vin Scelsa's podcasts with his daughter Kate Scelsa. And read all of our FUV Essentials features.