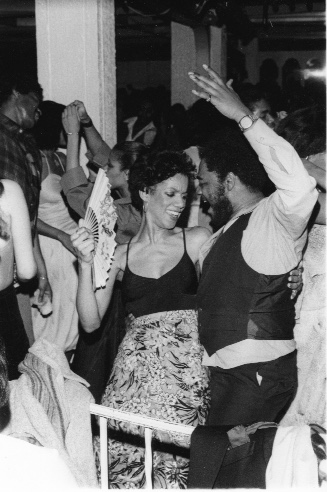

Celebrating Black Pride through Disco

Photo by Alix DeJean

NICOLETA PAPAVASILAKIS, host: Tell me about the ‘Best of Friends’ and some of your clubs.

NOEL HANKIN, guest: With five discotheques, Leviticus, Justine's and Bulgars in Manhattan, Lucifers in Queens and Brandies in Brooklyn, we attracted 400,000 people a year. So we had a really big time impact on the disco era before it really exploded in the general population.

NICOLETA PAPAVASILAKIS: Taking us back to the seventies, what was the disco scene like from what you remember?

HANKIN: There was really no disco scene. There was dances with live bands and house parties with recorded music. And the technology for recorded music had developed so well that there was the capability to deliver powerful crystal clear music for the first time at an affordable price. And we took advantage of that to entertain Black folks who were working in Midtown Manhattan in growing numbers in entry level managerial positions.

PAPAVASILAKIS: What was the impetus for this, you know, breaking into an industry where really there was no representation at the time?

HANKIN: That's correct. I went to a birthday party one day at a club called Le Martinique. It was a couple hundred folks, mostly African Americans, and they were dancing like it was Saturday night to recorded music. And I thought, you know, the dances are great, but this crowd that I'd like to tap into in Midtown Manhattan, they've never experienced anything like this with recorded music after work, dancing like a Saturday night and I thought that sounds like a lot of fun.

PAPAVASILAKIS: Today we have techno music and house music and it can all get blurred in this mash of disco. So at that time, what truly was disco?

HANKIN: What really happened was that the convergence of soul, r&b and funk led to the development of what we call disco music. In the early years of our discotheques we played music that had lyrics and I love the lyrics because they give you a sense of emotion and a context like you know, “Ain't No Stopping Us Now” by McFadden and Whitehead.

(SOUNDBITE OF “AIN’T NO STOPPING US NOW”)

Or James Brown “I'm Black and I'm Proud.”

(SOUNDBITE OF “I’M BLACK AND I’M PROUD)

These songs have lyrics that give you a certain emotion and they're positive and they're uplifting. When you get to techno music with no lyrics it's more mechanical and yes, it lends itself to dancing but you don't have the same emotion.

PAPAVASILAKIS: Can you describe the type of feelings these songs emoted - that these songs and these lyrics emoted for you?

HANKIN: When James Brown dropped that record “Say it loud, I'm Black and I'm proud,” that really resonated because you know, it took a little bit of a beat for people to accept Black pride in that context, you know, “I’m Black and I'm proud,” you'd never heard that phrase before. But it was something that was fully embraced by all of our guests and beyond.

PAPAVASILAKIS: Emerging into this new industry of disco, did you face any adversity at the time?

HANKIN: Oh, yes, we did. Our first club in Queens was Lucifers and we didn't have a problem with that. But when we went to Manhattan and built out what became our flagship Leviticus, we were looking at the East side because that's where our successful promoted discotheques were, you know, where we promoted other people's clubs and brought our crowd but we couldn't find a place on the East side. Finally, we did find a nice place and they wouldn't let us sign a lease because eight young Black guys in our twenties…they didn't know who we were, they might have thought we were, you know, into drugs or in a gang or something. I don't know, but they refused to sign a lease with us.

PAPAVASILAKIS: So after all that trouble when the ‘Best of Friends’ was finally able to open this club, what kind of crowd did you guys attract?

HANKIN: Not all African Americans. We had a lot of whites, hispanics, gays, straights everyone came because it was the only club of its type that featured music the way we played it.

PAPAVASILAKIS: Just elaborating on that, why do you think your clubs attracted such a diverse crowd?

HANKIN: We created an environment where you felt comfortable asking anyone to dance. So you might have a CEO dancing with a mailroom clerk or secretary and it didn't matter. Once you're on the dance floor your station in life is irrelevant and there was a certain amount of freedom involved with that.