Bronx Connections: Faces of Gun Violence (Part 5 of 5)

WFUV News, in partnership with The Norwood News and BronxNet Television, presents a five-part series on the impact gun violence has had on Bronx neighborhoods and the people who live in them.

How Developing Street Smarts Begins at Bronx Schools

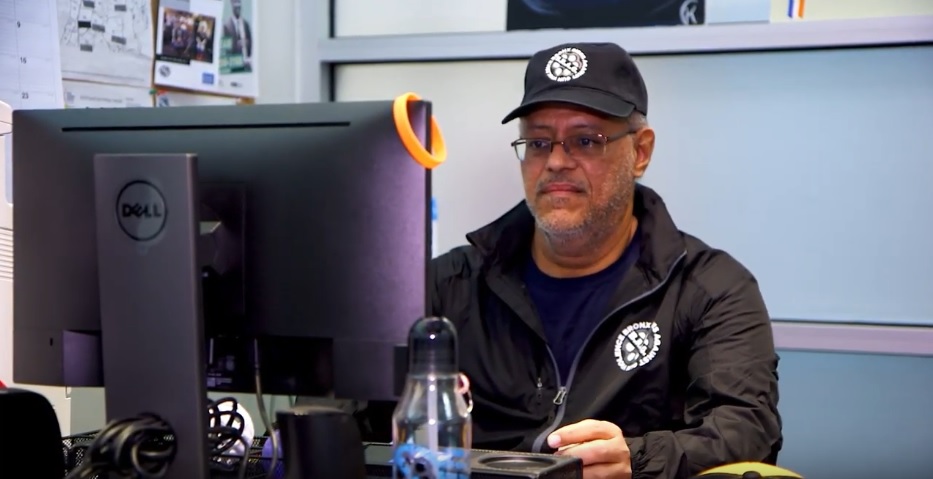

David Caba, senior program director of Bronx Rises Against Gun Violence (BRAG), sits at his desk at the organization’s office in Wakefield. It’s the newest office for BRAG, which utilizes a cure violence model adapted from a smaller model first implemented in Chicago.

The cure violence concept approaches violence like a disease in need of a cure. Caba built the program from the ground up, even creating the ubiquitous gray and blue logo while serving as a scout for where BRAG’s services are needed.

And in Wakefield–where incidents of gun violence are much more prevalent compared to other parts of the Bronx–the program could very well help stem the tide of gun-related incidents and reverse course for at-risk youth, as it’s done in other neighborhoods.

“It’s about gun violence, right? So, this was an area that I knew really, really well from both sides of the track,” Caba says. “It wasn’t that difficult for me to come in and understand what the model was, who the staff had to be, and how to implement this.”

BRAG now has three locations and 25 so-called violence interrupters working throughout the community. There are wraparound services to support the work being done in the streets, including a recently developed partnership with the city Department of Education. Schools, particularly intermediate, which serve as a breeding ground for gang recruitment. Caba would know. He was recruited by a gang in middle school.

For Caba, in his current role, education officials weren’t exactly bringing out a welcome mat for BRAG. “I didn’t get a whole lot of welcoming [from the schools]. We look like a gang. We speak a certain way, dress a certain way, talk a certain way,” he says.

Caba developed a strategy to get the schools and the kids to trust him. When students were dismissed at the end of the day, violence interrupters waited in the schoolyard to mediate any conflicts. Caba says school officials saw the method worked and were convinced in talking with BRAG.

A key player in those talks was Yadira Moncion, a location director at BRAG. She was part of the many meetings to secure a school conflict mediation program, which works with students to improve attendance and academics along with reducing violence. Moncion had to educate the community and schools about the importance of this program because it was a foreign concept.

“At times when you hear school conflict mediation you think we’re Superman or have

superpowers. So, it’s really educating them about the steps and what we actually do, which is to educate the youth and change that mindset, but taking a different route through academics,” says Moncion.

BRAG has worked in three schools–MS363, MS15, and Walton High School–since 2018. Moncion, has been in the human services field for 15 years, says the school conflict mediator works with students after school and has extended services during the school day. She says kids in the community need someone who they can relate to, and in BRAG’s case that someone is Michael Alvarado, BRAG school conflict mediator. He opens up to kids about his earlier years to let them know they can trust him.

“By the age of 18, I was shot, stabbed, got my head cracked open, got my nose broken a few times. And I was actually pronounced dead on the operating table-twice, from two different incidents,” Alvarado says. “So I was a high-risk youth. I wanted to live that street life when in all reality I was a nerd.”

“These kids are trying to find themselves, they’re trying to figure out their identity. They’re also chemically insane because they’re going through puberty, and then they have life issues and real circumstantial issues that are going on,” Alvarado says. “And there weren’t any credible messengers working with these kids who could say, ‘Hey, I know what you’re going through; I know what it’s like to be you and this is how I progressed out of that.’”

Alvarado says it’s one thing for someone to tell kids what their issues are, but it’s another to work with them through their hardships. Alvarado utilizes group sessions with students to talk with them about their troubles, but also make them realize the bigger picture.

Students who work with Alvarado tell him he’s only there because they’re troublemakers. Alvarado consistently countered that belief, arguing that he sees something in them they’re yet to see in themselves.

For Alvarado, having a role model like he is now for his younger self, might have helped him realize he was a numbers and statistics guy after all.

Caba, a Bronx native, served as a substance abuse counselor for many years and familiar with Bronx streets. He launched the program in New York by going into the community by himself. As time went on he realized he needed more help from credible messengers who lived in the community.

“The key to getting those individuals or crews to put the guns down, to stop the violence is hiring credible messengers who used to be those individuals from those very same neighborhoods, that are still living there, that are still relevant. Those are the ones they’ll listen to,” Caba said.